Cybernetics as discourse

“a discourse of effective organisation”

There are many definitions of cybernetics used by scholars from divergent disciplines, and no one of these can be held above the others on unshakable grounds. While some of its prominent definitions refer to it as an art, or something else altogether, cybernetics is most commonly referred to as a science. I would wager that many of its originators would unwaveringly defend its status as a science and find some of its subsequent uses confounding.

Nevertheless, the appropriate definition of cybernetics has more to do with the uses one is putting it to than anything else. It is not an inert body of literature to penetrate, but a diverse body of systems and objects; whether textual, aesthetic, performative, mechanical, or whatever else. For my own purposes, Stafford Beer’s definition is the most preferable I have come across. However, there are a couple of details I would rather alter. He calls cybernetics “the science of effective organisation”. I would prefer to rephrase it as: “a discourse of effective organisation”.

- “a”/”the” -

I say ‘a’ because it is not the only subject which pertains to effective organisation. Other subjects, such as political ideologies (anarchism and communism, for example) also discuss how society might be effectively organised, through various means and on various grounds. As Bill Cooke rightly pointed out to me, the definitiveness with which cybernetics has been categorised as the science of this or that is indicative of a hubris that might best be rejected.1

This same sense of exceptionalism over other disciplines leads me to take cybernetics to be transdisciplinary ("cross over, pass through") rather than metadisciplinary ("higher, beyond;") since to my mind, while cybernetics moves between whatever domain of thought it desires, it need not be understood as standing over and above them.2

- “science”/”discourse” -

Cybernetics is a science, in both the ‘soft’ (based on human culture, organisation, psychology, and so on) and the ‘hard’ sense (based on mathematics, psychiatry, physics, biology, etc). It was born out of an attempt to find common ground between a wide range of (scientific) disciplines and sought to decipher the mechanisms that could be attributed to all of them.3

On the other hand, applications of cybernetics have, from the outset, often exceeded the disciplinary remit of the sciences.4 Many of the founding cyberneticians applied themselves to domains not ordinarily referred to as sciences.5 Those who use it frequently refer to scientific concepts but they need not be scientists, even if they might be called cyberneticians.

Cybernetics is and always has been a science, but it has never only been a science, it has always exceeded its limits and branched out into distant, creative, and speculative areas of interest. It has always been at ease investigating the unorthodox, the spiritual, the expressive, and the emancipatory. What delineates the boundaries of cybernetics is less the confines of science and more the confines of discourse itself.

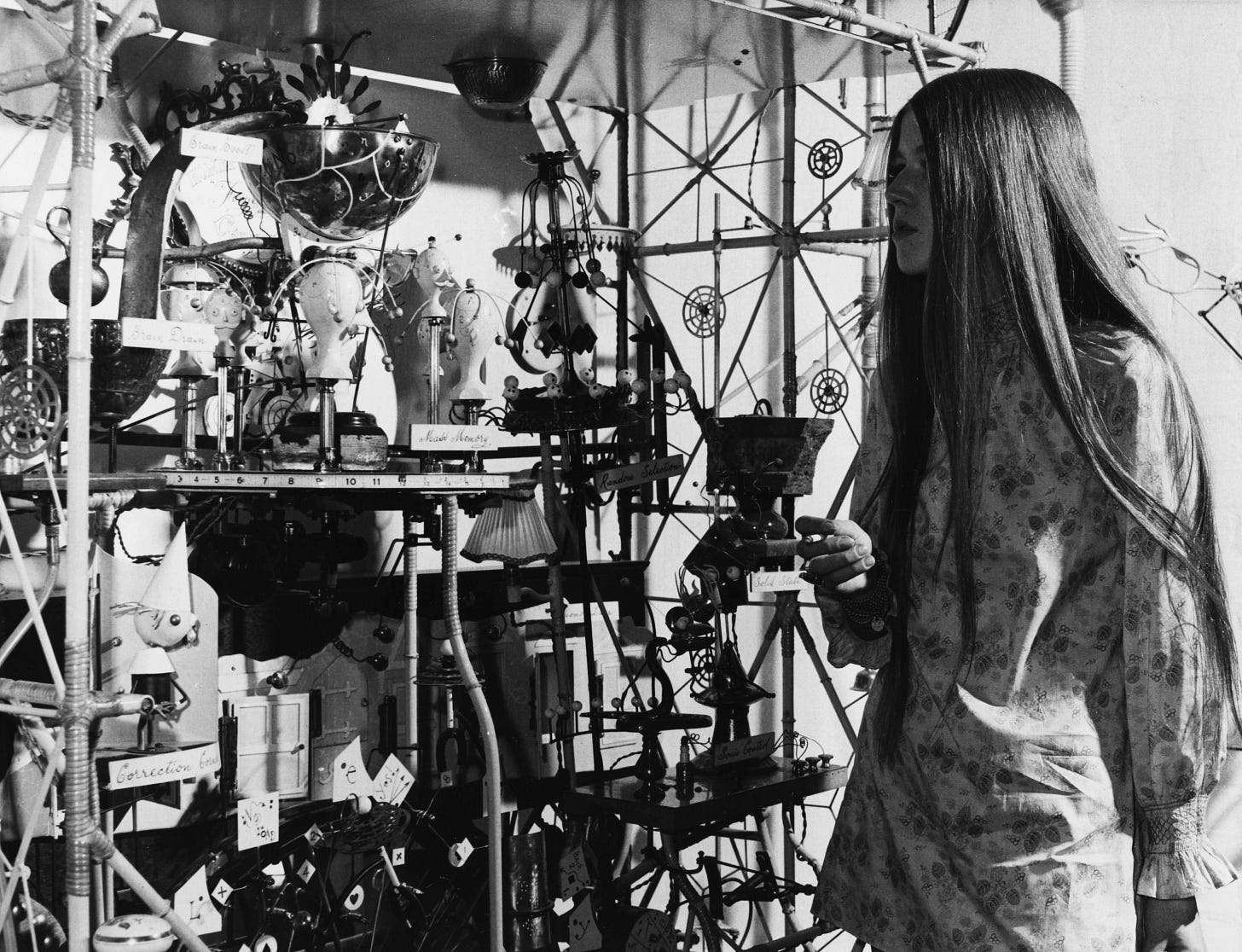

Cybernetics is a language (translanguage?); one which is expressed not only through the mediums of text and voice but through machines, technologies, practices, and productions of whatever kind. Objects such as those presented at Cybernetic Serendipity in 1968, Gysin’s Dream Machine, Price & Pask’s Fun Palace, and Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies challenge the view that cybernetics can be contained by institutional or disciplinary restrictions. Cyberneticians have routinely investigated the relationship between cybernetics and theological, spiritual, and magical dimensions of reality; Stafford Beer, Gregory Bateson, John Lilly, and even Wiener to name a few who come to mind.

Every system of language directed towards the elucidation of a complex system, whether they be scientific, philosophical, magical, imaginative, whatever, is an opportunity for cybernetics to familiarise itself with a new discourse, a new domain to accustom itself to. Cybernetics as discourse can be applied to whatever language game. The sciences are a particular set of language games that cybernetics emerged from and has always sought to exceed.

How one defines and applies cybernetics is a function of the goal one puts it towards, and the language with which it is expressed. Sometimes those purposes are scientific, but often they are something more. Cybernetics - expressed through a language and a medium - is oriented around its practitioners’ purpose and is consequently best understood in relation to that purpose.

-

Living cybernetics:

[01.21.14]: Cybernetics as “the art and science of manipulating defensible metaphors” (Gordon Pask). Later [1.35.32] Lombardi says: “I think that’s embedded in Pask’s definition, it is an invitation to any observer to define it as they see it. That’s the beauty of some of these definitions that don’t make sense.”

“They believed that the ability of cybernetics to model all organisms from the level of the cell to that of society, and its universal language of information, feedback, and homeostasis, made it a universal science, one that could unify such fields as biology and the social sciences”

- Kline, How disunity matters to the history of cybernetics in the human sciences in the United States.

Andrew Pickering: "Walter’s 1953 book The Living Brain is largely devoted to the science of the normal brain and its pathologies, epilepsy and mental illness. But in different passages it also goes beyond the pathological to include a whole range of what one might call altered states and strange performances: dreams, visions, synesthesia, hallucination, hypnotic trance, extrasensory perception, the achievement of nirvana and the weird abilities of Eastern yogis and fakirs—the “strange feats” of “grotesque cults” (1953, 148) such as suspending breathing and the heartbeat and tolerating intense pain.” (The Cybernetic Brain, p73)

Andrew Pickering discusses Beer’s work on the spiritual, god, tantra, etc (p278-290)