Towards a Viable Commons Model

Archetypes of Viability

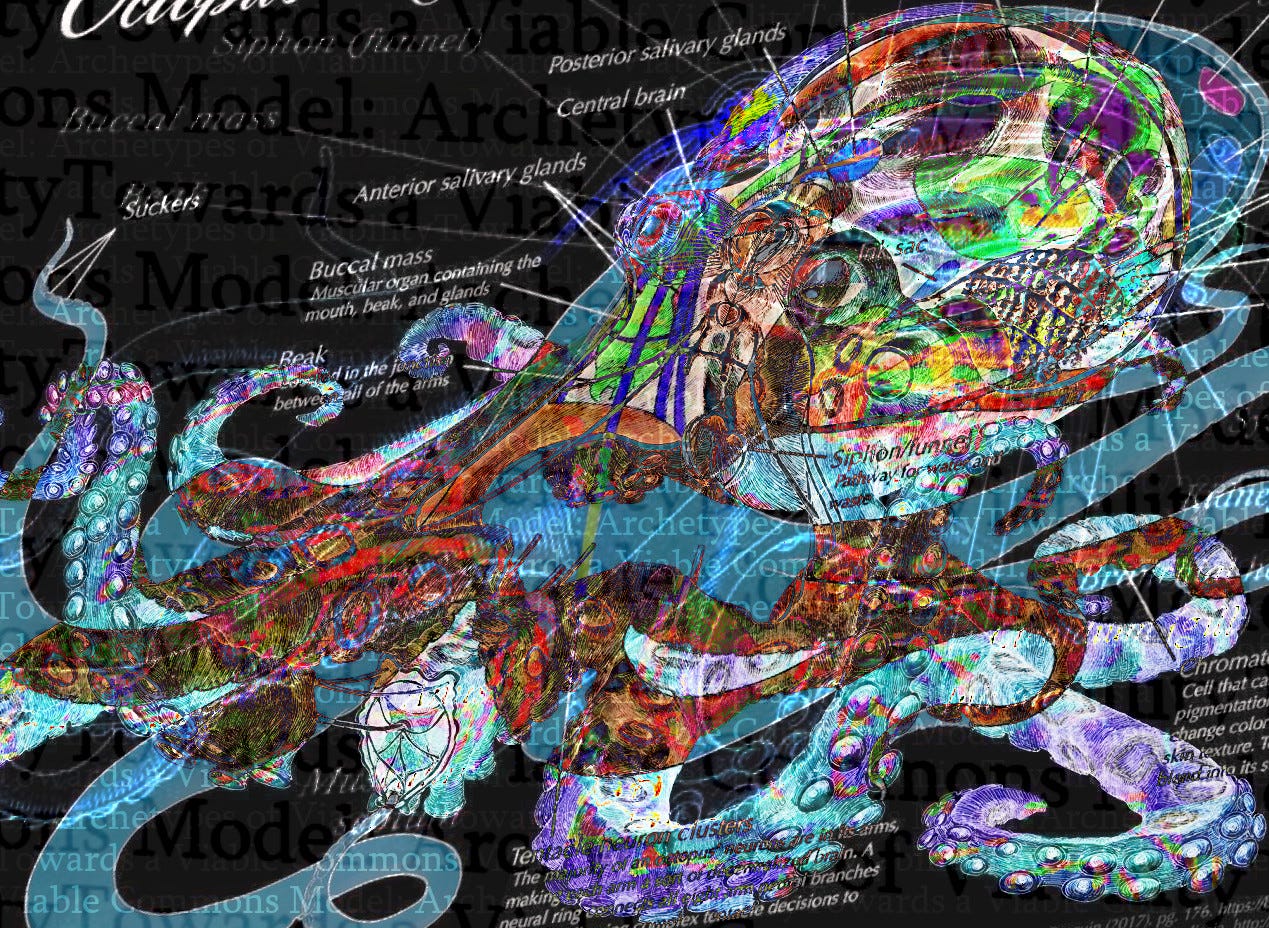

“We could have used another viable system - such as the amoeba, or a whole animal species- as the model. The results are the same, as they must be if viability as such has its own laws and enshrines its own principles (as cyberneticians contend).” (Beer, Brain of the Firm, p75)

“When biologists look at a bird, a mammal, even a fish, they are able to map many parts of one animal’s brain onto another’s. Vertebrates all have common architecture. When vertebrate brains are compared to octopus brains, all bets - or rather, all mappings - are off.” (Other Minds, Godfrey-Smith, p51)

Here, I’ll elaborate on one section from my last article, regarding the system upon which the VSM is based: the human nervous system. I will consider how the selection of this reference system, or as I will refer to it, homomorphic referent, has conditioned the way the VSM developed, and suggest that a different referent could be better mapped onto common organisations.

The homomorphic basis of the VSM

Viability emerges in complex systems in many forms and across vastly changing environments. Invariances exist between these systems from which we can learn a great deal. The study and elaboration of these invariances is the basis upon which cybernetics builds, and it is the job of the cybernetician to extract invariances from among those systems and articulate commonalities in clear terms. This is the goal that Beer sets about in his Viable Systems Model.

The VSM claims to articulate the necessary and sufficient criteria of a complex system being viable, and I believe it does an excellent job, at least in meta-systemic terms.1 Despite the VSM succeeding in its core goal of providing a framework which can be projected onto any very complex system as a means of analysis and diagnosis, it is worth considering the referent upon which the model is based in it’s specificity. My central claim here, undoubtedly controversial in some cyberentic circles, is that had another viable system been chosen as the basis of the model, the resulting form the model took may well have been otherwise.

Homomorphic referent as unintended steersman

There are certainly traits in common between different viable systems, as Beer argues, but this does not imply that the selection of any grounding model will lead to the same result. The selection of a homomorphic referent matters; it conditions the way the model manifests and how it is interpreted. This is because while every criterion of viability is contained within every viable system, as Beer claims, different viable systems may nonetheless draw one’s attention to particular aspects of viability, and not others.

The human nervous system is a hell of a viable system, but it doesn’t represent some archetypal or neutral image of viability which other systems must conform to, nor is it the most successful example of viability by most measures.2 Our nervous system, despite its capacity to be deconstructed into an invariant self-regulating structure, is unique and particular. Like any complex system, it has strengths and weaknesses, areas of emphasis and areas of relative indifference. Despite the dominance of humans in today’s world, it is merely one viable system among a great many others, and a relatively centralised one at that (when compared to both the examples offered below).

If we want to apply the lessons of the VSM to common organisations in particular, perhaps different grounding metaphors will offer a more appropriate foundation. Furthermore, perhaps it is not one homomorphic referent that we need, but several, to address and illustrate the diversity of common life. This begs the question, what specific forms of complex organic systems offer helpful homomorphic referents when considering common organisations?

Other models of viability

If we want to devise a model of viability specifically geared towards commonality, it follows that we should select a referent that is particularly appropriate to the context in which we want to utilise the model. In common cybernetics, we do not merely want to assist any old human organisation in becoming more viable, but particular types of organisation which further our common ends. We should therefore base any new representation of the VSM on reference points which are similar to the types of common organisation we seek to develop, in one way or another.3

Different organisms excel in different regards, and these others may provide more insight into a specifically common model of the viable system. For the time being, my attention is drawn to two complex systems in particular, which I plan to further investigate in the light of these insights. These organisms, I claim, tend to emphasise aspects of viability which are left underdeveloped in Beer’s model.4

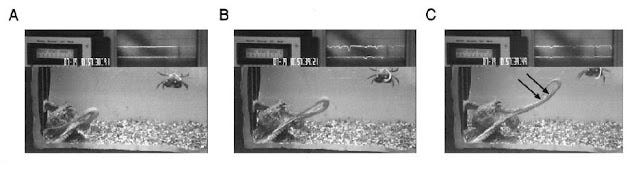

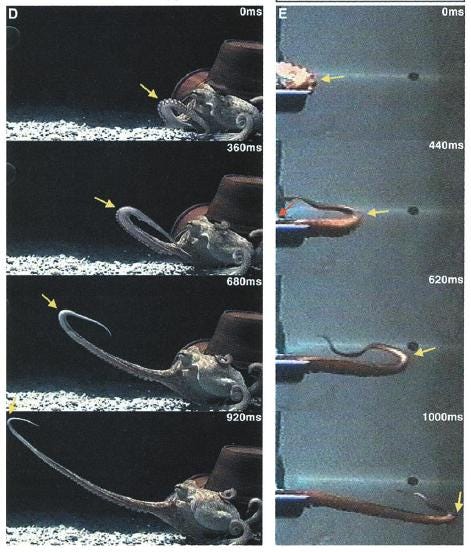

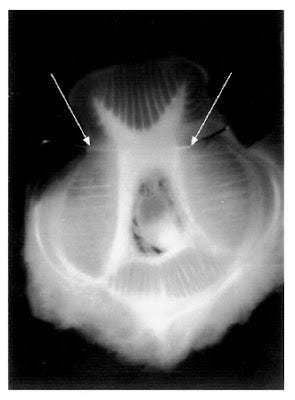

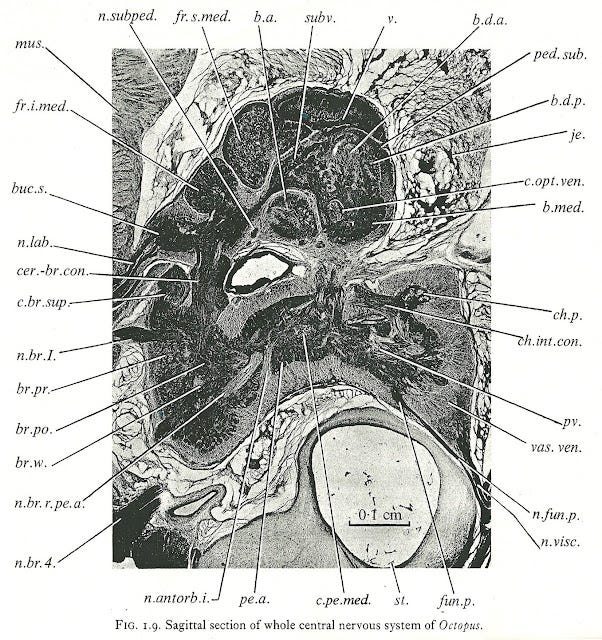

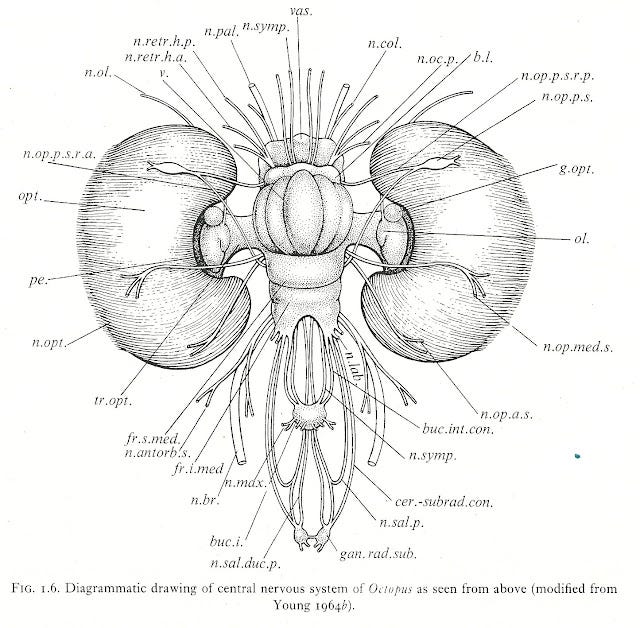

Cephelapods

The first is the octopus, or rather, cephalopods in general. There are two traits in particular that drew me to become quite obsessed with the cephalopods in recent weeks. First, they are the closest things to complex alien life which we can encounter and study. They are, on a biological evolutionary level, the furthest things from Beer’s chosen system in focus, which retain a comparable complexity and intelligence. Cephalepods are profoundly different from anthropods as a whole, and may therefore offer insights into how biological systems remain viable that step decisively away from Beer’s anthropomorphic starting point. Second, and more importantly for the study of the VCM in particular, is the extreme decentralisation of the cephalopod nervous system. While Beer, to his credit, spends much time emphasising the autonomy of operational units within the VSM, it is clear that human physiology is relatively centralised when compared with many other viable systems, cephalopods being an excellent example. If we are to consider the specificity of viability in common organisations, it makes sense to consider an organism with a highly distributed nervous system. The nervous system of the cephalopod is distributed throughout its entire body, with two-thirds of its neurons being located throughout its eight arms. An octopus thinks and even sees autonomously with its arms and skin.

On the other hand, cephalopods also have a trait which limits their similarity to commons-based organisations: their deeply solitary nature. While operational autonomy can be beautifully captured by the octopus and its kind, if we want to investigate sociality and solidarity, another organism comes to mind…

Ant colonies

To investigate the limits of cooperation, solidarity and sociality, I believe the selection of a living thing which is not an organism at all, but rather a super-organism, is a good place to start. Termites or bees could have been selected for this purpose, but I’ve always had an interest in the activities of ants. While they are quite unremarkable in isolation, they are incredibly powerful as a crowd and have profoundly intelligent emergent attributes. As a superorganism, they are even more decentralised than cephalopods, since they do not have a ‘brain’ at all, only a multiplicity of activity resulting in emergent behaviour. Another aspect of ant viability which draws my attention is related to an individual ant’s relationship with its environment. A huge part of an ant’s environment is, I think, other ants; in other words, its colony is its environment. This is true to such an extent that an individual ant, separated from its colony, is barely viable at all; it is ill-equipped to live in an environment in isolation, in profound contrast to the cephalepod. Consequently, in relation to ants, I intend to investigate not only the colony as a whole, but two systems at once. On the one hand, the superorganism that is the ant colony itself, for its incredible social intelligence, and the individual ant, to better understand the relationship between viability and the social environment it occupies.

Each of these complex organic systems, I believe, offers such different points of focus from Beer’s own model that they are bound to offer insights that were left implicit or ignored altogether in his own work, especially in relation to the commons. I have an intuition that each of these organisms might offer insights into two key under-developed aspects of the VSM alluded to above: operational activities and environmental interactions, as cephalapods excel in the autonomy of the former (while remaining linked to a meta-system), and ants excel in the latter (specifically in terms of interactions with other ants in the environment… in other words, cooperation).5

Nevertheless, this is the project I’m setting about, and my intuition tells me that it could lead to a real innovation with the VSM. Who knows where this research will lead, but I hope it will mark a progression towards greater viability in common organisations. More to follow.

I am sympathetic to some of the proposed changes and additions which have emerged since, particularly those discussed by Lassl in VSM 2.0.

There is no single objective measure of viability. There are, however, a few strong measures which might be indicative of viability. The age of a system is one good indicator, and the variety of environments in which the system can remain viable might be another. While humans are undoubtedly too young to score well on the first of these criteria, they do very well with the second. But if we take viability to be indicated by a system’s ability to retain the viability of its own environment, modern society seems uniquely unviable in its self-destructive thirst for growth.

This is not to say we should reject human physiology altogether or Beer’s model. It is very good at describing the meta-system in detail. I suspect that looking at the brains of different organisms wouldn’t add much in this regard. However, I believe, due to the relative centralisation of the human nervous system, that a disproportionate emphasis was placed on the meta-system in Beer’s work. This happened to be quite convenient for the managerial context in which the model was applied. It is also a subject I plan to discuss in more detail in future articles.

Although I do not want to elaborate in this short article, I will at least state what I mean here a little more specifically. By taking the human nervous system as his model of choice, Beer takes arguably the most well developed meta-system in the animal kingdom as his system in focus, while spending much less time considering either the operational components of viability (which he simply calls S1s) or the environmental conditions of viability, about which he says little. I look forward to elaborating on this in an article to come.

Having said this, I don’t want to reductively link one type of system to a particular aspect of the VSM in an overly simplistic way.

Really compelling angle on Beer's centralization bias. The octopus comparision is spot-on for commons work - thier distributed cognition is exactly what you need when operational units can't just ping headquarters for every descision. I worked with a decentralized mutual aid network once and the coordination problem was brutal because we kept trying to build "brain" structures when we needed "arm" structures. Your point about ant colonies as environment-for-each-other is interesting too, though I wonder if that gets you close to eusocial dynamics which might be its own trap. Looking forward to seeing where you take this.

What I'm either misunderstanding or missing in this, my first read on the topic, is the relationship *between* the various autonomous, local systems — i.e. the individual arms of octopi, or else individual ants within a colony. For a local system to be responsive, it must be either self-directed, or else directed by way of a proximal directorate. Local systems can not respond when they're directed remotely. This is a lesson I wish many organizations would learn.

Might small, local systems be modular? Might small, local systems be small, local systems *because* they're modular? If so, then how may modular systems move in concert? What motivates them?

???